Most large organizations operate with a standard business cycle that moves linearly from strategy development through execution to evaluation. While this approach provides clear accountability, it systematically creates blind spots that cost companies millions in misaligned initiatives and implementation failures.

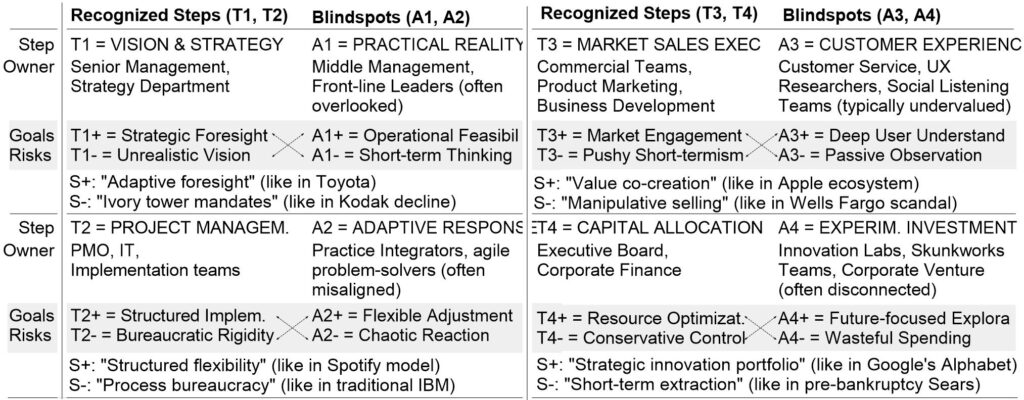

Our dialectical analysis reveals that for every recognized step in the business cycle, there exists an equally important counterbalancing function that often remains invisible to leadership.

Key Discovery: Reality checks and other corrective mechanisms must occur precisely in the middle of the cycle—not sooner, not later. Too fast correction compromises novelty, while too slow correction diminishes grounding.

This optimal positioning creates a natural self-regulating system with both forward momentum and built-in correction. Our framework identifies organizational “acupuncture points” that improve performance without requiring disruptive restructuring.

1. Problem

Most large organizations operate with a standard business cycle that follows a predictable sequence:

- Start with vision/strategy (T1)

- Convert to concrete plans (T2)

- Execute in the market (T3)

- Evaluate and adjust (T4)

However, this linear approach comes with significant hidden costs. McKinsey research shows that 70% of complex, large-scale change programs don’t reach their stated goals (Bucy et al, 2016).

The root cause lies not in implementation failures but in the cyclical structure itself. By separating complementary functions in time and organizational space, traditional business cycles inadvertently disable natural feedback mechanisms that could otherwise create self-correcting systems.

Here we introduce a dialectical approach to business cycle analysis that identifies systemic blind spots and provides a framework for resequencing organizational processes to create more resilient and adaptive operations. See the “Dialectics for Systems Optimization” for philosophical background.

2. Identifying Blind Spots

Our method identifies critical factors through semantic analysis of functional oppositions. Every business cycle’s step or owner (T) is provided with two marginal descriptions: the constructive (T+) and potentially destructive (T-) aspects of its functionality or operation. The direct semantic oppositions of T+ and T- identify the complementary steps or owners (A) that dialectically balance the T’s actions. These are essential counterbalancing mechanisms that create systemic resilience:

This analysis identifies four categories of professionals whose contributions are of comparable importance to the recognized groups, yet frequently lack appropriate influence or timing in the business cycle:

- Middle/Front-line Managers provide operational feasibility insights crucial for testing vision against reality, yet often lack voice in strategy formation. Their practical knowledge serves as an essential counterbalance to strategic ambition, preventing unrealistic initiatives before major resources are committed.

- Practice Integrators with agile problem-solving capability – typically experienced professionals with deep knowledge of the company’s informal capabilities – provide the adaptability essential to implementation success. These individuals navigate between formal structures and informal networks, overcoming obstacles that rigid project management frameworks cannot anticipate.

- Customer Experience Teams hold deep understanding of user needs that should inform sales approaches but are typically consulted too late in the process. Their insights create the essential balance between market engagement and customer value, preventing short-term sales tactics that damage long-term relationships.

- Innovation Investment Teams create future value streams but are commonly separated from mainstream resource allocation decisions. Their experimental approach balances conservative capital allocation, ensuring the organization explores new opportunities while optimizing existing operations.

Each of these represents a systemic ‘blind spot’ in the conventional business cycle. When properly integrated through dialectical analysis, they transform linear processes into robust, self-correcting systems that create positive synthesis (S+) as shown in the table—like Toyota’s ‘adaptive foresight’ or Apple’s ‘value co-creation.’ When neglected, negative synthesis (S-) emerges, creating problematic outcomes like Kodak’s ‘ivory tower mandates’ or Wells Fargo’s ‘manipulative selling.’

3. Optimum Sequencing

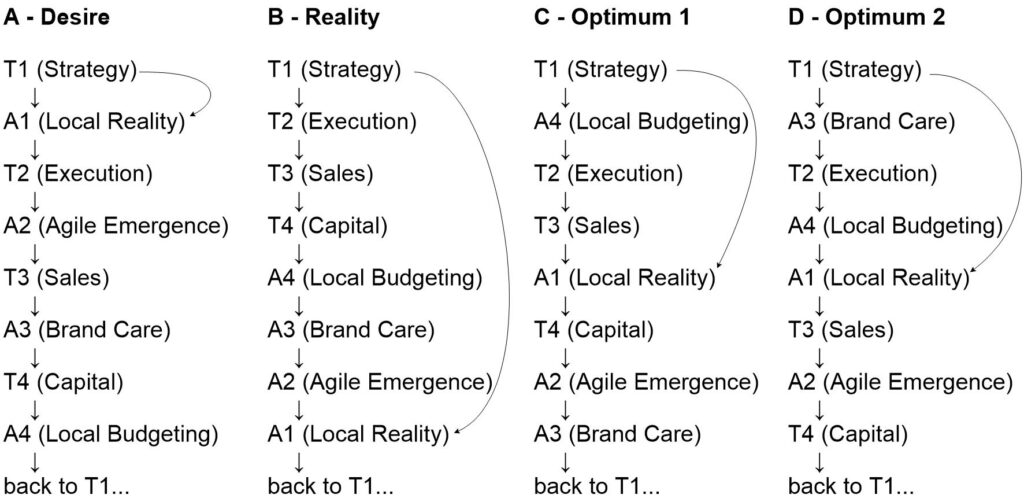

Once we identify blind spots, how do we integrate them into the business cycle for maximum effect? Fig. 1 presents four possible sequencing approaches:

Scenario A shows the intuitive approach: moving directly from strategy (T1) to reality testing (A1).

Scenario B illustrates what commonly happens: reality testing is delayed until the final step of the cycle.

Scenarios C and D demonstrate the optimal placement: reality testing positioned in the middle of the cycle. This follows a key dialectical principle – maximum complementarity occurs when opposing elements are placed diagonally across from each other in the cycle. The optimal mid-cycle placement works because:

- Early reality checks (Scenario A) compromise strategic innovation before it’s fully developed

- Late checks (Scenario B) waste resources on potentially flawed initiatives

- Mid-cycle placement (Scenarios C/D) balances forward momentum with corrective feedback

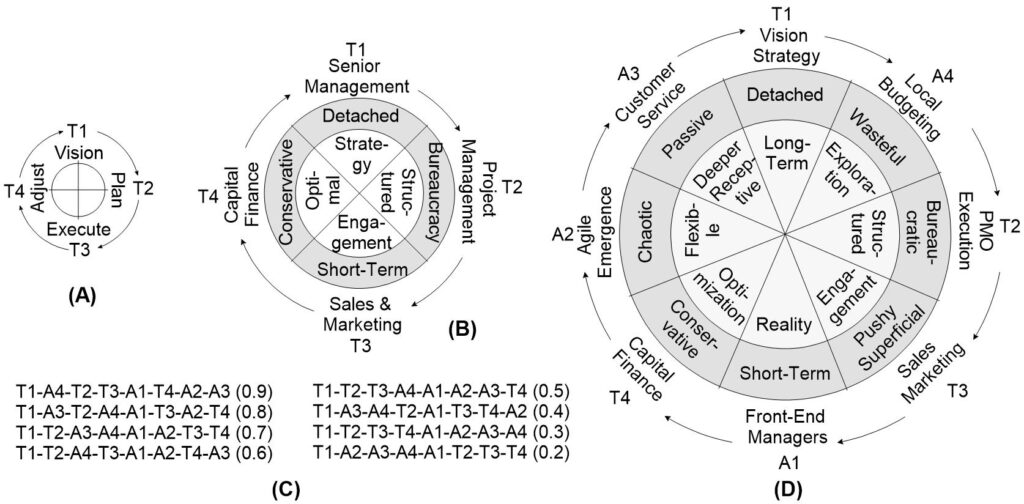

The following schemes illustrate the development process toward optimal sequences.

Scheme A shows the starting cycle, scheme B – the positive and negative aspects that were used to identify the antithetical domains. Scheme C shows possible causal arrangements that preserve both diagonal relations and natural business flow. The most effective sequence (probability 0.9) is:

Strategy → Local Budget → Execution → Sales → Local Reality → Capital → Agility → Customer Care

This sequence uniquely positions Local Budgeting immediately after Strategy, enabling faster execution and more effective reality checking before major capital allocation and internal restructuring occurs.

This analysis highlights the critical importance of agile process integrators (A2) who:

- Have deep institutional knowledge

- Know how to make things work

- Navigate formal and informal systems

- Connect people across silos

- Take personal ownership of outcomes

These individuals are instrumental in determining successful capital absorption and should be identified and supported by both senior and project management.

Scheme D shows the complete roadmap combining both the natural causation and diagonal complementation through informal cooperation. The latter acts as a centripetal force, holding the cycle together and spiraling toward positive synthesis at the center.

4. More Specific Effects

While we’ve examined the general business cycle, every organization faces unique situations. Small contextual differences can significantly alter the critical control factors. Table 2 demonstrates this by showing how different antithetical domains emerge for various senior management functions.

For instance, when addressing culture creation, department heads become the critical counterbalancing force, while for capital allocation, intrapreneurs take on this essential role.

This specificity reveals that each situation has its own “magic touch” – targeted interventions that improve system-wide performance while remaining invisible to linear management thinking. By identifying the precise problem, we can pinpoint organizational “acupuncture spots” that create disproportionate positive impact without requiring disruptive restructuring.

Similar extended analysis can be made for the remaining steps of the business cycle (T2, T3, T4), as well as any other steps not considered here. The dialectical approach is universally applicable across all organizational functions, revealing hidden complementary relationships that traditional management frameworks often miss.

5. Conclusion: Transforming Business Cycles

Our dialectical analysis reveals that business cycles can be transformed from linear processes into self-regulating systems through strategic resequencing of complementary functions.

Organizations can implement this approach by:

- Identifying their specific blind spots

- Positioning reality checks in the middle of the cycle

- Supporting process integrators who bridge formal and informal systems

This framework addresses the root cause of change program failures rather than just symptoms, offering a practical path to improve the 70% failure rate of large-scale organizational initiatives without requiring disruptive restructuring.