“Most corporate mission statements are worthless. They consist largely of pious platitudes such as: ‘We will hold ourselves to the highest standards of professionalism and ethical behavior.’” (B.R. Cassady and T. Gueorguiev, citing Ackoff, 2004)

Big firms love big missions. But dialectically, those promises create equally big—and unintended— shadow sides. Consider the Mission and Vision of GM:

Provide all-electric vehicles for everyone while safely pushing transportation beyond imaginations, aiming for a world with Zero Crashes, Zero Emissions, and Zero Congestion (Comparaibility)

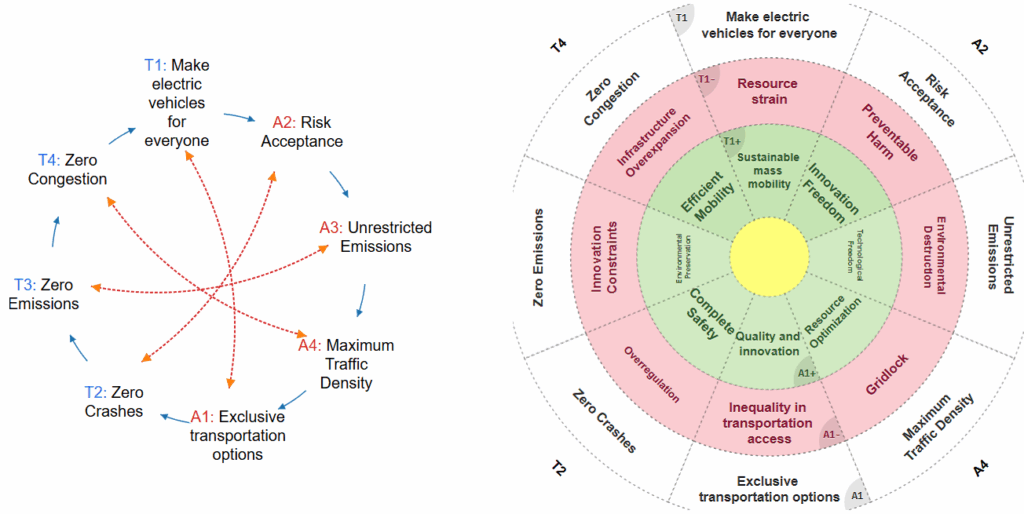

Feeding this into the Eye-Opener algorithm generates the antitheses and arranges everything into an optimal causal map:

The first wheel suggests a likely sequence. In the near term we accept more risk (A2), see higher upstream emissions (A3), and experience greater traffic density (A4). These pressures tend to make mobility more exclusive (A1). Only after this might the system swing toward the intended theses—Zero Crashes (T2), Zero Emissions (T3), and Zero Congestion (T4)—and, last, the ambition of making EVs for everyone (T1).

The second wheel points to higher subtleties. Inside (green) are the intended benefits; outside (red) are the unintended harms —the counter-effects that predictably appear when we begin with absolutized goals.

- Pushing “EVs for everyone” lights up resource strain and infrastructure over-expansion: more mining, grid demand, land use, and capital intensity to universalize a heavy technology.

- Aiming for “Zero Emissions” at the tailpipe throws shadow into the unrestricted emissions upstream (extraction, manufacturing, electricity mix) and potential environmental destruction where materials are sourced.

- Promising “Zero Crashes” pulls stress into human-machine handover risks, over-regulation or innovation constraints, and higher cognitive load for drivers as supervision duties shift.

- Targeting “Zero Congestion” creates pressure toward gridlock elsewhere via induced demand and maximum traffic density if added capacity simply fills back up.

In short: the future-perfect promise concentrates attention on what’s easily measured in the spotlight, while significant costs disperse across blind-spots—nervous stress, upstream harm, dependency on opaque IT, and unequal access.

None of this argues against electrification or safety. It argues that absolutizing the goal (“Zero everything”) hides the costs that arrive now unless we name and manage them.

A better, balanced mission and vision

Here is the reframing that aligns ambition with obligations and the dialectical insights above:

Mission: Deliver reliable mobility with year-over-year reductions in total lifecycle emissions, extraction, injuries, stress, and inequity—tracked with paired thesis–antithesis metrics and bounded by public harm budgets.

Vision: A mobility ecosystem where fewer miles meet more needs—right-sized electric fleets, excellent transit and active travel, data-respecting automation, and products built for repair, reuse, and return to earth.

This framing keeps the aspiration but dials back the absolutism. It makes space for real trade-offs—material sufficiency instead of more-for-everyone by default; lifecycle accounting instead of tailpipe-only wins; human-factors safety, not just crash counts; and mode diversity so that “mobility” doesn’t equal “more driving.”

That’s the point of the Eye-Opener wheels: not to dismiss bold visions, but to complete them—so the shadow side is visible, accountable, and actively managed rather than paid for quietly by people and places off-stage.