Our problem isn’t scarcity—it’s rule inflation and metric fixation (Power; Muller; OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook).

Today’s global challenges arise less from natural shortages or any “villain nature” of humankind than from an exaggerated reliance on rules and regulations (Ostrom Polycentric Aproach, 2009).

Because power tends to corrupt, rulebooks often reflect the interests and blind spots of rule-makers (Stigler, The Theory of Economic Regulation, Niskanen, Bureaucracy and Representative Government), shrinking the ‘common good’ into utilitarian metric targets (Power, The Audit Society, Muller, The Tyranny of Metrics). Instead, we should optimize each person’s capacity to recognize and fulfill their intimate obligations—discerned individually and in context (The Capability Approach). Regulation should therefore default to advisory guidance that cultivates discernment, with mandates reserved for only a few child-clear red lines (Responsive Regulation).

Why centralized rules underperform

No central code can pre-compute what’s right across diverse contexts, as knowledge is dispersed (Hayek), many public problems are wicked (Rittel & Webber), and effective governance is polycentric (Ostrom; Scott).

When regulation over-specifies the how instead of the why, systems get brittle: compliance rises, judgment atrophies, and perverse incentives multiply. We end up outsourcing conscience to paperwork. Worse, when rules treat citizens as latent offenders, people adapt to the low expectation—fear scales; trust shrinks (Tyler et al., 2015, Psychological Science in the Public Interest).

Serve the regulated — not an abstract “common good”

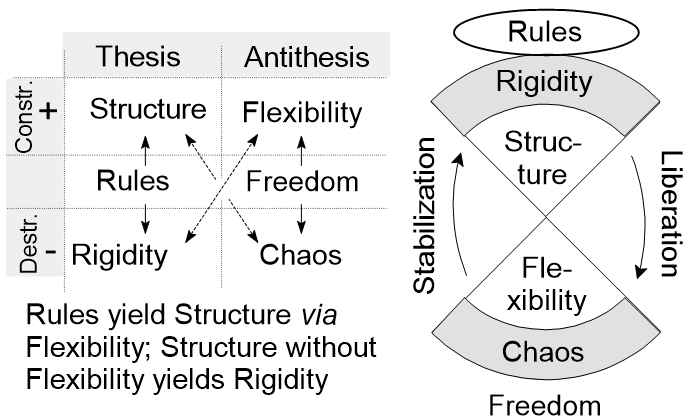

Policymakers aim for the “common good,” but policies backfire when counter-virtues are ignored. In a dialectical ethic, a practice is “good” only while it cultivates the positive side of its opposite—for example, safety that also grows autonomy and independence, or order that also grows initiative. When rules suppress their own counter-virtues—creativity, adaptability, responsibility—they become harmful (see Redefining Good and Bad). The aim of policy, then, is to grow not a “common good”, but rather everyone’s capacity for obligation-taking.

This standard must begin with those who design and enforce rules. A regulator has moral and practical standing only insofar as they recognize and cultivate the positive side of the position they constrain. When regulators engage that counter-virtue, compliance becomes capability-building rather than mere restriction. In practice, this means turning policies into growth maps that specify the complementary virtue each rule must develop. Regulators then become like peaceful warriors (as in the film Peaceful Warrior): servicing their counterparts rather than pursuing personal gains.

A new posture

Flip the baseline.

- Advisory by default. Publish clear principles, transparent boundaries, and feedback loops—then allow “safe-to-try” variation (Responsive Regulation).

- Mandatory by exception. Escalate to mandates only past a few, child-clear red lines (e.g., clear harm thresholds, critical infrastructure). Keep mandates narrow, outcome-based, and revisable as competence grows (Transcending the deregulation debate).

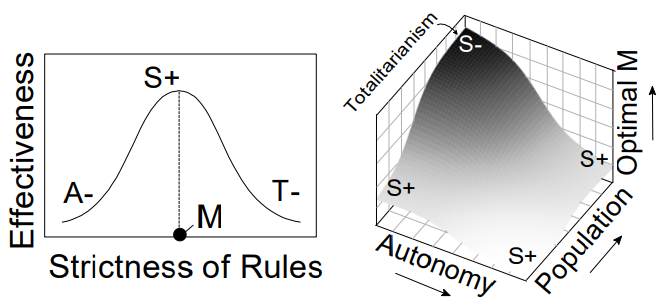

This posture creates a freedom gap—space where individuals practice discernment and build “skin in the game”. In turn, this yields higher effectiveness through self-regulation:

These dependencies are backed by many studies (see references at the end). Together, they suggest that strictness is chiefly a function of self-reliance and context: as autonomy and diversity rise, the optimal strictness M falls—and systems become safer because people are stronger.

Turn policies into growth maps

Structured dialectics turns policies itno growth maps. Start by identifying the positive and negative aspects of a policy and its meaningful opposite (the dialectical pair):

Then use AI (and expert review) to propose actionable transitions that convert a negative in one component into a positive in the other. In practice, this yields a repeatable pattern:

- Keep the principle, loosen the procedure. Write the non-negotiables; run bounded experiments that honor them. Review outcomes, not paperwork.

- Name zones. Publish stability zones (must follow) and freedom zones (may vary). Iterate based on measured effects.

- Graduate discretion. Expand freedom as teams demonstrate competence and integrity.

Every policy gets a positive antithesis and a set of actionable transitions between them—your growth map. (See examples here.)

Objections, answered

- “Without strict rules, people misbehave.” Sometimes; which is why red lines exist. But chronic over-control breeds dependency, evasion, and hypocrisy. Responsibility matures in supervised freedom, not in zero-variance labs.

- “Advisory rules are vague.” Only if principles and metrics are vague. Publish the why, the boundaries, and how you’ll measure success; let the how emerge locally.

- “This is anti-safety.” No—this is pro-resilience. Mandate proven harm-reduction where warranted; simultaneously cultivate judgment so safety doesn’t collapse the moment supervision lapses.

Design implications

- Legislate the why. Statutes should name purposes and red lines; procedures live closer to practice and evolve quickly.

- Audit outcomes, not forms. Reward real results and learning, not box-ticking.

- Make trust the default. Assume good faith (presumption of innocence – not guiltiness); monitor transparently; escalate proportionately.

- Teach for discernment. Fund “responsibility sandboxes” in mobility, health, finance—bounded arenas where citizens practice judgment and see consequences.

The civic ethos we need

Tacitus cautioned that proliferating laws signal a decaying republic.

“The more corrupt the state, the more numerous the laws.”

— Tacitus, Annals (Book III, chapter 27)

Our answer isn’t anarchy; it’s complementarity: rules that amplify human uniqueness rather than dominate it. When policy is designed to cultivate the positive side of its opposites, we get citizens who can do the right thing especially when no one is watching:

One-sentence takeaway: Make rules that make people bigger than rules—advisory by default, mandatory past red lines—and we’ll trade brittle compliance for genuine growth.

References

- Black, J. (2008). Forms and paradoxes of principles-based regulation (LSE Law, Society and Economy Working Paper 13/2008). London School of Economics. LSE+1

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2010). Cooperative behavior cascades in human social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(12), 5334–5338. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0913149107 PNAS+1

- Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530. University of Chicago+1

- Hollnagel, E. (2014). Safety-I and Safety-II: The past and future of safety management. Ashgate. Amazon+1

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press & Assessment+1

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press. Wikipedia

- Sull, D. N., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2001). Strategy as simple rules. Harvard Business Review, 79(1), 106–116. Harvard Business Review+1

- Sull, D. N., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2015). Simple rules: How to thrive in a complex world. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Harvard Business Review

- Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2001). Managing the unexpected: Assuring high performance in an age of complexity (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass. [See also 2nd ed., 2007.]